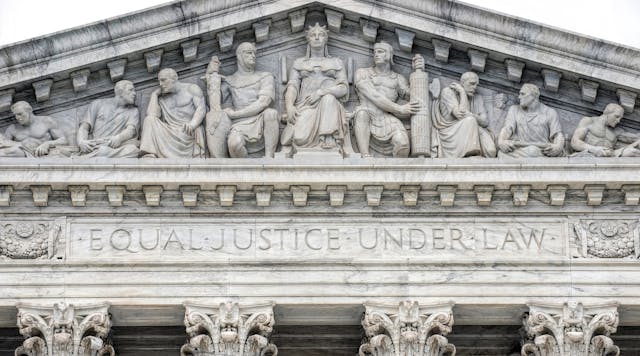

Two recent decisions from the U.S. Supreme Court that failed to get appropriate coverage from the news media are expected to have a major impact on businesses, including one that extends their tort lawsuit liability geographically to states where the injury did not actually occur, and another case where the court finally defined the legal term “undue hardship” for employers who seek to accommodate workers’ religious beliefs.

Although the court’s decision regarding affirmative action in university admissions policies is and will remain for the foreseeable future the single most historic decision of this term, these other two positions staked out by the court will reshape the daily world that employers work in and color their policies and plans regarding their employees’ needs for the foreseeable future.

In the case of Mallory v. Norfolk Southern Railway Co., a partial majority reversed the dismissal of such a case and upheld Pennsylvania’s corporate-registration statute, under which out-of-state corporations that register to do business in the state automatically consent to general personal jurisdiction in Pennsylvania. In this case, Pennsylvania’s Supreme Court joined other states in finding the registration statutes violate due process rights.

At least 20 other states also have similar statutes on their books. Although the details of the statutes—and the string of court decisions that have interpreted them—vary significantly, these statutes purport to authorize general personal jurisdiction over out-of-state companies based solely on a company’s registration to do business in that state. Apparently, the Supreme Court now agrees that these kinds of statutes do not violate due process, at least for the time being.

Called a “sea change” by dissenting Justice Amy Comey Barrett, this decision upends a series of the Supreme Court’s own decisions over the last nine years that had sharply restricted general personal jurisdiction over out-of-state corporations. However, the court did leave open that this new legal view could be challenged under the U.S. Constitution’s Commerce Clause.

Many private attorneys have emphasized the importance of this case for employers, including P. Russell Perdew, J. Matthew Goodin and Bella Seeberg of the Locke Lord law firm. “In the short-term, companies should expect plaintiffs to engage in forum shopping in any state where the company registered to do business under a statute similar to the one in Pennsylvania,” they said. Out-of-state defendants facing such claims should be knowledgeable regarding the details of the state statute on which the plaintiff bases jurisdiction and be prepared to challenge jurisdiction under the Commerce Clause theory left open in Mallory.

In this particular case, a worker living in Virginia sued his former employer, a Virginia corporation, claiming the employer should be held liable for injuries he sustained while he was working in the states of Virginia and Ohio. But instead of filing suit in Virginia or Ohio, the plaintiff filed his claims in a Pennsylvania state court.

Why did the injured worker originally choose to file his claim in Pennsylvania? The plaintiff contended that because the company had registered to do business there and Pennsylvania law provided that registration constituted consent to be sued there, the state’s courts had jurisdiction over the company and the dispute he had brought, note attorneys Rachel Owsley and Daniel Boswell of the law firm of Stites & Harbison. Because the process of registering to do business in a state or withdrawing from a state was previously seen generally as a simple matter of corporate housekeeping, the Supreme Court’s decision raises the stakes, Owsley and Boswell point out. “The implications for employers cannot be exaggerated.”

They also suggested that the only consolation is that the new precedent may turn out to be relatively short lived, according to many attorneys, who point to the odd voting arrangement on the court, which ended up creating a 5-4 majority because Justice Samuel Alito chose to only concur in part with four other justices.

While rejecting the due-process challenge, the majority also stressed that employer defendants could potentially challenge registration statutes under the Commerce Clause. “The interesting 4-1-4 split of justices along non-typical ideological lines emphasizes just how unusual the decision is and foreshadows how it may turn out,” Owsley and Boswell note. “The court left the door open to further litigation to re-establish limits on general jurisdiction.”

They also observed, “While some of the court laid out other potential flaws of such state laws, for now especially, companies should carefully monitor their state registrations to ensure they are in line with their current business activities.”

Defining Undue Hardship

In a separate decision called Groff v. DeJoy, the justices also made it easier for employees to obtain religious accommodation from their employer in a case where a U.S. Postal worker had been fired for refusing to work on Sundays.

Federal civil rights law has long held that employers must grant a reasonable accommodation for an employee to protect their right to the free exercise of their religious beliefs, as long as doing what the worker requests does not create an “undue hardship” for the employer. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) also requires reasonable accommodation for individuals with disabilities as long as that will not result in “undue hardship,” but the ADA more clearly defines what that means.

Up to this point, deciding what an undue hardship consisted of was determined on a case-by-case basis in the absence of any clearly defined standard.

Under the new standard announced by the unanimous Supreme Court decision, undue hardship will be found only if the accommodation “would result in substantial increased costs, in relation to the conduct of the particular business.”

Robin Shea, a partner with the law firm of Constangy Brooks Smith & Prophete, explains, ”As a practical matter, this means that larger employers may have a difficult time prevailing on an undue hardship defense because they can presumably absorb more of the cost of accommodation. However, the court did not adopt the even more demanding standard that applies to disability accommodations under the ADA and other, newer, federal statutes.”

The High Court also made clear that the impact on co-workers will not be considered an “undue hardship” if the co-worker objections are based on opposition to religious accommodation in principle or are based on religious-based prejudice. However, the court did leave open the possibility that certain other impacts on co-workers could affect “the conduct of the particular business” and thus could considered to create an undue hardship.

Determining what constitutes a “substantial increased cost” is currently undefined and will necessarily differ depending on an employer’s size, the nature and scope of its operations and other factors, point out attorneys for the law firm of Littler Mendelson.

“It is reasonable to surmise that this decision may impose a greater obligation on larger employers because demonstrating ‘substantial increased cost’ may be more difficult when there is a large workforce with talent presumably available to perform others’ work tasks and significant revenues or profits where the ability to bear the costs of accommodations are presumed,” they believe.

Shea stresses that in light of this decision, employers should be ready to field and seriously consider many more requests for religious accommodation. As a result, Shea offers employers these suggestions:

• Require requests for religious accommodation to be made in writing, with exceptions for employees who are not fluent in English or who have literacy issues. The request should contain a brief explanation as to how the employer’s policy or practice conflicts with the employee’s religious beliefs.

• Review the requests, and make sure they are really religious in nature. With COVID vaccines, many employers received “religious” accommodation requests that were not based on religion but on politics or fear about the safety of the vaccines. Those may be legitimate concerns, but they are not “religious” in nature.

• If the request is religious in nature, assess whether the employee’s belief is sincerely held. When in doubt, assume that the belief is sincere.

• If the request is religious in nature, and if the employee’s belief appears to be sincere, then either grant the accommodation request or go through the ADA “interactive process” with the employee before making an “undue hardship” determination.